The following is a tribute written by his son, Joe Sills. Photo gallery at bottom of article.

Sills Era of Sonic Excellence Silenced After 78 Years

COVID-19 claims a pioneer of Mid-South music and a lifelong teacher of thousands.

-Joe Sills

Cordelia brought him there. The band needed an extra trumpet for their new year’s gig, and the man at the front called on a young boy from Brownsville, Tennessee to complete the job. By the time midnight struck, Carl Perkins and his band had torn the house down, and the boy from Brownsville who hitched a ride with his mom had been touched by a spotlight that would grace him for the rest of his life.

Joseph Robert Sills of Brownsville, Tennessee passed away on January 15, 2021 due to COVID-19 at 78-years-old. By the time his spotlight faded, Sills was known by many titles: trumpet player, band director, Kentucky Colonel, writer, angler, father and “Papa Joe.” In the course of a life that held at least three chapters, he shared his light with thousands.

Joseph Robert Sills of Brownsville, Tennessee passed away on January 15, 2021 due to COVID-19 at 78-years-old. By the time his spotlight faded, Sills was known by many titles: trumpet player, band director, Kentucky Colonel, writer, angler, father and “Papa Joe.” In the course of a life that held at least three chapters, he shared his light with thousands.

In 1960, the silver trumpet that brought Sills on stage with one of the founding fathers of rock n’ roll took him to the music program at Memphis State University. There, he studied under the tutelage of Dr. Tom Ferguson and became one of the first horns to ever play alongside a basketball game at Madison Square Garden. That day, Memphis students unfurled a banner before his horn with a name that stands today, “The Mighty Sound of the South.” They were playing a new fight song that you can still hear at Memphis games today.

In college, Sills side-gigged with Stax Records and the chart-topping soul group the Bar-Kays. Often, he would wake up early after a night on the road and head to nearby lakes and ponds to go fishing, a treasured pastime borrowed from his father. Sills graduated Memphis State with a bachelors in music education in 1964 and completed his masters in the same field in 1971. And as the city of Memphis was hitting its pinnacle as an innovator of popular music, one of its sons was about to innovate the world of marching music just 60 miles away.

In his first post as band director at nearby Bolivar Central High School, Sills would blend lessons learned from Dr. Ferguson with his own, unique style of teaching and marching. He could play every instrument in the band with pitch perfect precession, and he could somehow teach high school kids to do the same while blaring at them from an obnoxious, ivory megaphone.

At Bolivar, Sills and the “Mean Green” marching band would team with New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath to usher his team off of the field to make way for the music during an AFL scrimmage at Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium.

His creative process was as unique as the powerful performances he produced. Often, long weekends on the lake would conjure images of moving formations meshed with sounds that translated into the classroom and the trophy case. Sills found that somewhere in the swirls of tepid, Tennessee water a source of limitless inspiration.

While completing his masters degree, Sills and the Bolivar Tigers—alongside his assistant director and lifelong fishing partner Bill Bradford—would capture three consecutive championships at the Mid-South Invitational, the area’s most prestigious high school marching band competition.

Fueled by early success on the field and visions of a thriving largemouth bass population at Kentucky Lake, Sills left Bolivar for Murray, Kentucky in 1972. It was a move that set him on a collision course with destiny.

Like Bolivar, the Tigers of Murray High School captured another string of three consecutive Mid-South Invitational Championships. But these Tigers reached unprecedented heights, as the ranks of the small town band swelled to encompass a third of the entire student body. These Tigers were twice called upon to perform in the Orange Bowl parade in Miami. They twice took home Kentucky State Championships. And in 1977, Murray High School claimed the Marching Bands of America Grand National Championship by out-marching and out-playing schools two or three times their own size.

Just like a golf win Augusta, this championship came with a permanent place in history and a signature jacket.

Sills took a hiatus from music after the national championship before returning to West Tennessee to lead another band of Tigers onto the field, the Ripley Tigers. In Ripley, he would help claim another three-peat at the Mid-South Invitational from 1981 to 1983, culminating with an appearance invitation to the Florida Citrus Bowl. The run cemented him as a nine-time Mid-South champion and a legend in the world of music education.

By the mid-1980s, nearly three decades had passed since Cordelia “Peggy” Sills drove a young boy with a trumpet to a one-off gig with Carl Perkins. After the Citrus Bowl season, she was beginning to need more help around the house. And when a job opened up in his hometown of Brownsville midway through the 1984 season, Sills seized the opportunity to spend more time with his aging mother and fill the trophy case that eluded him for thirty years—the one at Haywood High School.

Fate had other plans for his return.

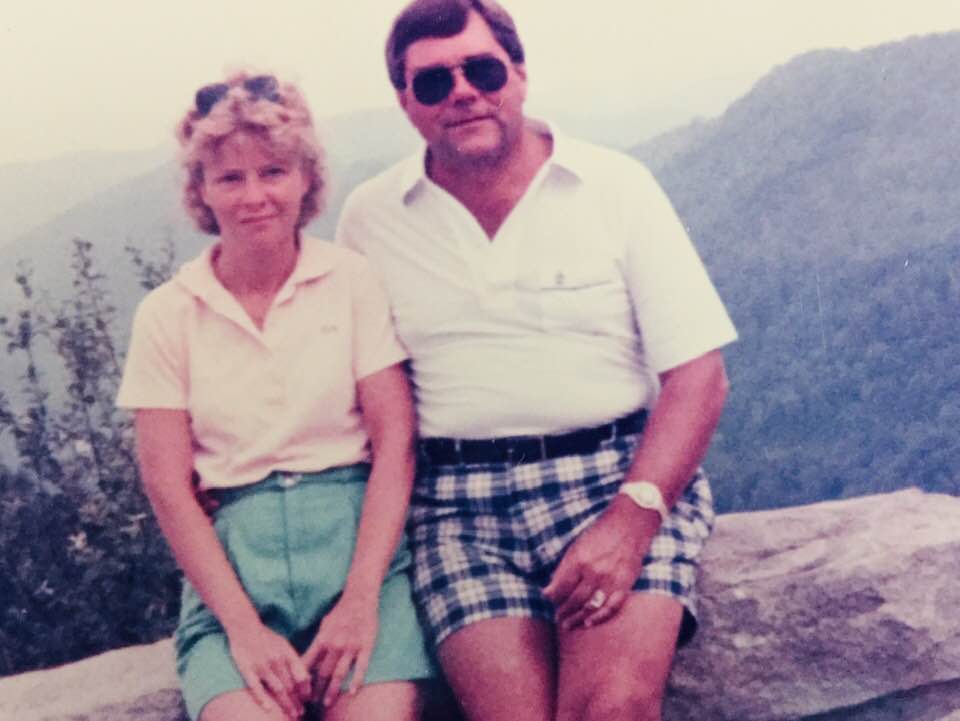

In Brownsville, Sills met a young elementary school teacher and opera singer being towed down a small town street by a Saint Bernard. Her son happened to be a middling saxophone player in the Tomcat band, and after an on-again-off-again pursuit, the two were on for good. Within a year, Joe and Susan Sills were married. They soon had a son, a fourth for Susan and a first for Joe. Reports are that the saxophone player was not impressed by the wedding, but was finally appeased when he earned a promotion to the percussion section and a set of quad drums.

Under the direction of Sills, the Haywood Tomcats band did indeed reach new heights, but when the popularity of the band began to outpace that of the storied local football team, creative differences cut short the pursuit of another Mid-South Invitational championship. In 1992, Sills moved his band program up the road to Dyersburg for a final chapter in music education with another stepson—this time a talented virtuoso—on French horn.

Three years later, Sills would retire his signature megaphone for good and begin laying plans for his final chapter. Predictably, it was a chapter that revolved around the lake.

In 1997, Sills joined forces with another Brownsville native, Carlton Veirs, to swell the ranks of subscribers for his regional outdoors publication, the Mid-South Hunting & Fishing News. It was a role that fit Sills like a glove. His intimate knowledge of the area’s fisheries had been growing since the 1950s. In fact, while school trophy cases had filling with band awards, Sills had been plastering his personal trophy shelf at home with gold plated bass earned on the local tournament trail.

At the magazine, years spent networking with band members and raising funds for travel to bowl games and competitions translated perfectly into ad sales and outreach. Crucially, a job as an outdoor writer also meant Sills could finally earn a paycheck by fishing.

For the next 23 years, Sills devoted his life to teaching more people how to fish. He founded a bass fishing club for youth in his hometown, helped one member claim a pair of national championship in that sport and became the youth director for the entire state of Tennessee at fishing’s preeminent organization, B.A.S.S. Occasionally, Sills and Bradford would bump into another Bill in the backwater swamps of West Tennessee. This Bill went by the last name Dance.

As an outdoor writer, Sills lead a campaign to save his beloved Hatchie River from industrial and agricultural pollution. He was recognized by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service for his outstanding service. Along the way, he bridged the gap between state congressmen and river rats to get the job done. Fittingly, the Hatchie River flows near Bolivar, Ripley, and Brownsville.

The three sons that Sills adopted when he married Susan became business owners, artists, parents, veterans and college graduates. The fourth son enjoys a career as journalist and explorer who also works with Veirs.

The entire family can instinctively hook a fish. And they can all close their eyes and hear the familiar cadence of marching bands almost on command.

This week, Joe Sills, a 78-year-old field commander, is not marching to the beat of his own drum or under the rhythm of his own heart. He is marching into the Great Beyond on the wings of a soul that was sent to inspire. He was a devout Christian that believed wholeheartedly in fate. And he leaves behind an extended family of thousands clad in purple, gold, green and white. They are musicians, doctors, band directors, teachers, parents and scientists. They are the legacy of a life well-lived, the timeless treasures of a teacher.

When his body is laid to rest, Joe Sills will greet death with open arms, for he did not fear its embrace. In heaven, he will finally hear the sounds of angelic brass in harmony. They will mingle with farewell refrains echoing from the horns and hands of his students, gathered in tribute from new bands nationwide.

In the end, as in the beginning, Cordelia will be by his side.

Joseph Robert Sills was preceded in death his brother, Timothy Rains Sills; his father, Joseph Wallace Sills and his mother, Cordelia “Peggy” Rains Sills, and his beloved horse, Lady. He is survived by his wife Susan Speake Sills, his four sons, John Christopher Morey and wife Kelley, Evan Wallace Morey, Cameron Speake Morey and wife Rebecca and Joseph Lawrence Sills, along with 11 grandchildren and two nephews.

Services will be held at 2:00 p.m. on Saturday, January 23 at Oakwood Cemetery in Brownsville, Tennessee. An honorary band comprised of former students, family members and alumni will play music preselected by the former director. Social distancing and face coverings are required.