By Taylor Wilson

Editor’s Note: This Outdoor Originals column is published in MSHFN to tell about those unique characters you may have enjoyed fishing or hunting with, should the opportunity have presented itself. In this edition we are varying off a bit from sportsmen per se, and rather detailing someone that greatly contributed to hunters in the Mid-South.

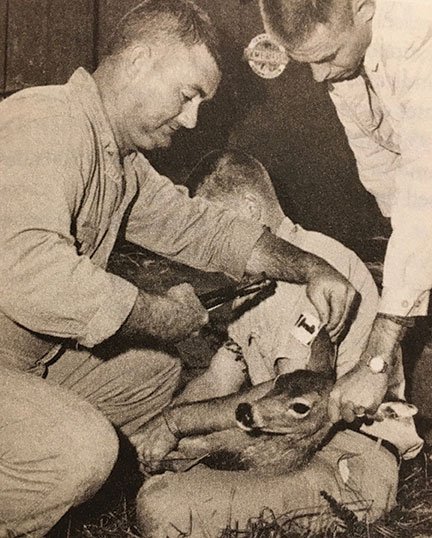

I first met biologist Joe Farrar when he worked for the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency and I worked for a daily newspaper covering the outdoors. Farrar was a pioneer in both the restoration of white-tailed deer and wild turkey in Tennessee. West Tennessee hunters should be especially appreciative of his efforts, for that is where much of his work was done, though he traversed the entire state.

I tried to track Farrar down for this article, but friends and fellow employees could only tell me that he had retired and was living in Murfreesboro with family. It my sincerest hope that he is doing well. I do always think of him when I marvel at a white-tailed deer or wild turkey and ponder how once these critters were very uncommon on our landscape.

It’s through the efforts of Farrar and other such personnel that hunters have had so many countless enjoyable hours outdoors.

When I first began interviewing Farrar for stories and information (late 1980s, early 1990s), he lived in Lexington, Tenn. The State’s deer herd was exploding, and harvest totals soared to new records annually. He reminded me of how this wasn’t always so, and how he had burned up many road miles, tanks of gas and tires hauling deer and turkeys to and fro in order to jump start their restoration.

“Oh, we’d have a press conference in the field,” he said of the initial deer releases. “We’d cut all the racks off the bucks, to possibly offer added protection them from would-be poachers. But sometimes we’d leave the antlers on a nice buck. We’d let that one out last, right before we’d say to the reporters and anyone that had gathered to watch: ‘This is the kind of deer you’ll have if you take care of these animals.’ That big deer and the rest would come out of the boxes wide open for the release. The cameras would flash, and we’d be off to plan another transport,” he told me.

Along about the time I first met him, Tennessee hunters begin becoming more and more interested in trophy management. Farrar having hands-on experience with deer for so long told something at the time I thought very interesting.

“What hunters need to realize is that it’s one thing to grow big bucks; it’s another to actually consistently kill them,” Farrar told me. “Oh, you apt to shoot a trophy now and then, especially if there are more of them around, but trust me on this, a mature white-tailed buck is a different critter, and it just isn’t going to give you as many opportunities to shoot him as will a 1 ½- to 2 ½-year-old buck.”

I always laughed at how prophetic Farrar’s words were, though at the time I remember thinking he was giving a deer’s wiles too much credit. He wasn’t.

Many West Tennessee sportsman should be grateful for Farrar’s efforts. His was a job well done, and he’s certainly an outdoor original.