Note: This is the first of a three-part series on Chronic Wasting Disease

I have always considered milestones to be achievements, but have come to understand they are much like riding in a speeding truck with the driver admiring the river, sunset, or deer and, me, the passenger, watching the road. Except for an occasional yip to help keep it all between the ditches, I miss most of the milestones. And life is that way. We miss the regularities of the natural systems functioning all around us, except when some notable change occurs. I remember when deer first became abundant in west Tennessee. I will remember when Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) was first detected.

Anyone seriously attempting to understand CWD will quickly find themselves immersed in voluminous stacks of technical literature and much of it written in the specialized language of a particular science. I have tried to keep this easily readable, but will occasionally wander off into terminology most of us do not use at the local coffee shop. Inevitably, some of these deals with the biochemistry class we all slept through, but there are no helping it. Our cells know more about us than we do.

If you suddenly discover a sentence akin to a junk yard dog hoping you will climb the fence, don’t worry about it. Just back up and go around. In my defense I would say too much has been written too blithely, and even wrongly, about CWD. To lend a little more insight I sometimes use the literary license of letting the reader get a sense of the depth of what is known about the disease.

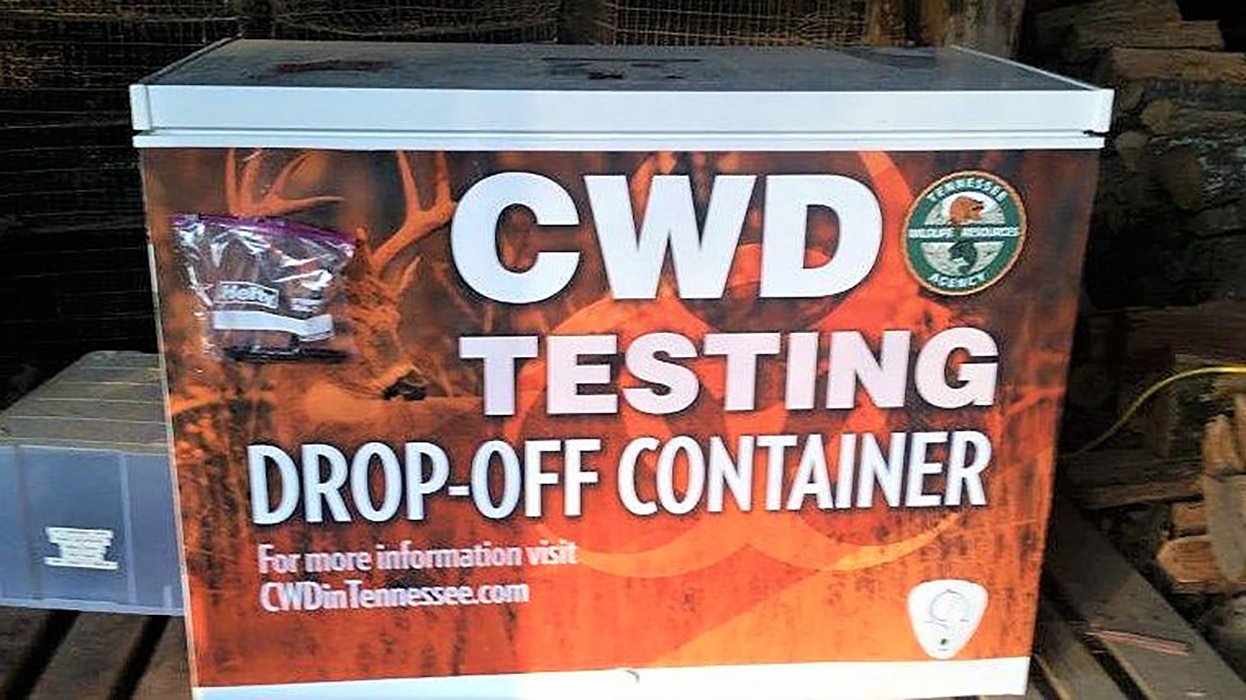

When CWD was discovered in North Mississippi in late 2018 a murmur of unease swept through West Tennessee as hunters hoped that would be it, just isolated cases and the deadly condition had not spread. It came as a “gut punch” when the TWRA reported 13 deer tested positive in late December and another 11 were announced in January. Since that time the news has gotten worse. More animals have tested positive and the range has spread across several counties.

CWD was first described in a captive herd in Colorado in the 60’s. However, as is true of many such things, the first observed is never the “first one out there.” As a result, it is unlikely its true origin can be known. In fact, those first cases where labeled as a wasting syndrome and were thought to be due nutritional deficiency or stress. It was 1978, when a mule deer in a Toronto zoo died, before the malady began to be properly characterized as a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE). The consensus is CWD either jumped from scrapie in sheep or had a spontaneous origin when a normal metabolic protein mutated.

As more cases were observed significant federal funding became available and CWD was quickly found in other parts of the west, leading to a mildly mistaken notion it was spreading like wildfire. In reality much of its early expansion on the map was related to looking for it. But it is spreading and currently can be found in 26 U.S. states, four Canadian Provinces and four foreign countries.

There are more than 200,000 different kinds of protein in our bodies, many with a purpose not yet understood. Each of our several trillion cells has huge numbers of essential proteins whooshing around inside them. Any particular protein is strung just right with amino acids and shaped properly to do its job. And, protein that misshapes and also becomes infectious is referred to as a “prion.” Once prions acquire their alternative shape they can highjack cellular processes and, somewhat mysteriously, hand out instructions to replicate themselves.

Prion science was developed by Stanley Prusiner, who won the Nobel Prize in 1977 for his work. The Nobel is not awarded without critically evaluated merit; and this is a sobering thing to consider when weighing the value of any new “theory.”

PrPSc which is a misfolded variant of normal PrPC protein and is the infectious agent behind diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob in humans, scrapie in sheep, mad cow disease and CWD, which affects members of the cervid family: deer, elk, mule deer, reindeer and moose. PrPSc is a hard nut due its insolubility and a nature to aggregate. The cervid prion is remarkably compact, with only 16 amino acid polymorphisms. Some of these polymorphisms have been associated with lower rates of CWD infection or slower progression of clinical symptoms. CWD is unique among prion diseases as being the only one known to infect free-ranging, as well as captive/domesticated animals.

Genetically influenced resistance is linked to atypical physical traits that are not beneficial, perhaps explaining why the population is not full of resistant deer in the first place. Resistance is a double edged sword. Any infected, resistant deer serves as a source for prions longer. But, as I will speculate later, the genome may hold significant keys in CWD’s eventual control.

Once prions are in a deer’s body they accumulate in the lymph glands first, move into neurological systems and eventually invade the brain where they clump and create microscopic voids, leading to a condition technically referred to as spongiform encephalopathy: or sponge brain.

If a deer is infected the condition is inevitable, irreversible and 100 percent fatal. There is no cure. There is no vaccine; and even if so, a delivery system into the herd would need to be ingenious.

In short, there are no magic bullets.

Infected deer typically live about 12 to 18 months after exposure and during much of that time appear to be just fine, although perhaps predisposed to other diseases or mishap. In a Colorado study, road-killed mule deer were 1.6 to 15.9 times more likely to be infected than estimated rates for deer populations local to the collision. In the last 6-to-8 weeks the animal begins to cease feeding, eventually becomes gaunt, unaware, drooling and has a braced up stance like a sawhorse, symptoms much akin to the latter stages of Alzheimer’s. However, the real tragedy lies with the prion itself.